OUR HISTORY

Okolona, a Brief History of Days Gone By

Written in 2000 by Celia Coleman Fisher

Commemorates Sesquicentennial: 1850-2000

The historical marker near the southern edge of town reads: “Okolona, Founded as Rose Hill 1845. Chartered as Okolona 1850. Named for Chickasaw Indian Brave. Scene of three Civil War battles. First Mississippi Cavalry, C.S.A. was organized and equipped here.”

On the southern edge of an earlier Okolona, near that historical marker, stand approximately one thousand white marble headstones, marking the graves o victims of Shiloh, Brice’s Crossroads, Corinth and Okolona battles. Three hundred of these stones in the Confederate Cemetery, or “Soldiers Cemetery” read “unknown”. Other stones tell us their graves contain the remains of young men from Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, as well as Mississippi. Later in this history Okolona’s Civil War Battles will be discussed.

The cemetery is located next to the old “Citizens Cemetery”. In 1886 a city ordinance was passed regulating burial of the dead in “Citizens” old graveyard except to those having a portion of their family already buried there. A “new” cemetery was placed in the northeast part of the city. Today, there are a large number of former residents buried there. White and black cemeteries are located adjacent to one another.

WPA records verify that a small cemetery was situated due north of where the Confederate Monument now stands at the east end of Main Street in the downtown area. There were burials in it in the 1840’s and 1850s. Family records show that Wiley Kyle was buried here around 1850, and his wife, Catherine, a few years later. The existence of this cemetery is practically unknown to anyone now living and there is no trace of that cemetery today.

On the northern edge of town is the almost abandoned (part in ruins, part in stags of renovations), one thriving, Okolona College. This school for blacks was founded in 1902 as Okolona College. Its founder was a young graduate of Talledega and Berea Colleges, Dr. Wallace A. Battle. The school began in a dilapidated blacksmith shop. Eventually, there was a substantial campus composed of many buildings including classrooms, dormitories, sports fields and all the amenities of a learning institution of its kind. In 1920, it became affiliated with the Episcopal Diocese of Mississippi. In 1922, St. Bernards’ a mission of the Episcopal Church, as established at the school.

Several local white families supported the school and helped serve as liaison between the school and the community. Mr. A.T. Stovall served a president of the board until his death. Captain B.J. Abbott, for whom Abbott Hall was named, gave the first $1000 toward building costs. For many years, the school serv4d as the school for black students in grades nine through twelve. They were taught part academic and part trade classes.

In 1933, the school became, in addition to a high school, a junior college with emphasis on teacher training. In the 1949 yearbook, sophomore students in the college are listed from Weir, Nettleton, Houlka, Aberdeen, Amory, Moselle, Shannon, Ellisville, Shubuta, Hamilton and Artesia, as well as Okolona.

A study made in 1964 showed that 85% of all black teachers in a tri-county area were graduates or former students at Okolona College. All black band masters of the period had studied there. During the peak period, enrolment reached above three hundred students including day and boarding students. Until 1959, the county paid a mall tuition fee for the county’s black students to attend the “college” for their high school courses.

In 1965, after 63 years of service, the doors of the college closed. Times had changed. Okolona’s high school students had a school of their own. Fannie Carter High School had been built on Winter Street as part of Mississippi’s “separate but equal” program. The new school replaced the old Meridian Street School which had been located on the corner of Olive and Washington Streets. Meridian Street School (the street it was on was once called Meridian St.) had served grades one through eight. The new school was named Fannie Carter High School for a beloved teacher who had taught in the combination church and school, Mt. Pisgah.

Older students from Okolona and other towns were by the 1960s attending state supported colleges or universities. But for many, a void was left when the college closed. Today, there is an effort by local groups and alumni to restore the physical aspects of the college. To mention outstanding students, one would run the risk of leaving out many. However, William Raspberry, who attended the school and is now a syndicated columnist for the Washington Post, has written in his column about Okolona College and the fine background that it gave so many.

Mentioned above are descriptions of two landmarks. One is much more precious to one race, while the other is dear to another race. As is the case for any place int e South during the years following 1845, two histories could be written. For until 1970, when the public school were integrated under court order, very little interaction took place between most people of the black and white communities.

With integration, during U.W. President Richard Nixon’s term in office, Fannie Carter High School became Okolona High School serving grades seven through twelve of both races. At the same time, the former school for whites, located at the intersection of Main Street and Church Street (now Highway 245) became Okolona Elementary School, serving both races grades one through six.

The schools closed for two weeks in February of 1970 while books, desks, labs and such were moved to the proper campus. Teachers of both races busied themselves with getting the classrooms ready for the students. Some students and parents pitched in to help. There was great apprehension on both sides since no one knew the feelings of others. The senior classes that year, having been together less than a semester, had separate graduations and end of year functions. By the next fall, everything was combined and pretty much “children were children” and “teachers were teachers”. Not all was perfect, but those involved were determined to make it work. Most of the school population remained intact at that time, although some did transfer to Chickasaw Academy, located in nearby Van Vleet.

Discussion of the very earliest attempts at education in Okolona will be discussed later in this history.

Let’s go back, though, to a much earlier time. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if one could step back and, decade by decade, watch Okolona develop? It would be nice to know what life was really like for people living here during all one hundred and fifty plus years of our history.

In the 1840’s, with word that the Mobile and Ohio Railroad would come through were Okolona now stands, a settlement began here, usurping Prairie Mount which had developed six miles to the west. Before the building of the M&O Railroad through Chickasaw County, all of Its marketable products and the purchased supplies were transported on wagons to and from the Tombigbee River at Aberdeen, about thirty miles away. People traveled on horseback or some type of wheeled vehicle. For greater distances they may have gone by boat. The stagecoach stop in Okolona was on the northeast corner of Church and Washington Streets.

Okolona was not the original name of the community. It was Rose Hill. There were a couple of stores and a post office at Rose Hill. From the Post Office in Washington, D.C. came the order that the name of the little prairie post office must be changed. There was already another Rose Hill in Mississippi. Mr. Josiah Walton, in charge of the post office in Aberdeen was instructed to change the name.

Mr. Walton named the town Okolona for a Chickasaw Indian herdsman he had met years earlier in this vicinity, while enroute from Aberdeen to Pontotoc to visit his siters. Mr. Walton described the brave as the handsomest Indian he had ever seen – the perfect picture of a hunter and warrior. For his quiet manner and peaceful habits, the brave had been called Okolona (Oka-laua), “peaceful water”. There is some question as to the exact translation of the name, but it had to do with still or peaceful water.

By the time the little town in the Tombigbee Prairie was given the name, the Chickasaws had been removed from the area. Most of them marched to the reservation in Oklahoma, where many of their descendants live today. This might be an appropriate place to note that at Okolona’s celebration of 150 years, a group of present day Chickasaws were hired to come to their ancentral home and perform. For most of them, it was their first trip to the county named for them and the home of their forefathers.

In the year 1848, Honorable John J. McRae, later to be governor, came to the county as agent for the Mobile and Ohio Railroad and addressed the people at Houston. The company wanted to build a railroad like somewhere west of the Tombigbee River. There seemed to be very little interest by the people of the county in a railroad, with the exception of Judge T.N. Martin, who owned the only newspaper published at that time in the county. He set up times and places for public meetings about the railroad.

The first meeting was at Okolona, which was at that time a very young village with probably no more than two hundred inhabitants. It was considered a place of wealth, taste and leisure. Wealthy farmers of the aera were accustomed to meet there for pleasure, pastime and to transact business. Those present at the time of the meeting were polite and respectful after being coerced into attending. Very few stock subscriptions were obtained by the railroad continued the pursuit.

The railroad, already proceeding northward from Mobile, began to have more appeal to the people and gradually their attitude changed. The county subscribed for and paid by taxation %50,000 for assistance in building the railroad. Support of the citizens continued to increase and the tracks were completed to Okolona and beyond in 1859.

Okolona was chartered or incorporated in either 1848 or 1850. There are conflicting accounts. But it is known that H.L. Hill was its first mayor. Okolona quickly became the center of trade for Chickasaw County. Goods, especially cotton, were shipped from Okolona to far-away markets. The rich prairie soil surrounding the city was perfect for large scale cotton production.

Leading merchants, such as C.C. Dibrell, Buchanan and Son, and Myers and Housman transferred their businesses from Houston to Okolona. By 1859, there were six dry goods stores, two drugstores, a jewelry store, two saddle and harness shops, three blacksmith shops, three grocery stores, a tin shop, cabinet manufactory, a carriage shop, two livery stables, one funeral parlor and several candy, toy and liquor establishments. In addition, there were six lawyers, six doctors, a banking institution (the Savings Institute) and a newspaper, the “Prairie News”, which was first published in 1851. This was phenomenal growth for one decade.

Okolona was just coming into its own as a little city with lots of pride when the Civil War began. The town found itself in the path of the Federals’ objectives more than once. Actual combat took place here at there different times. The first raid took place in December, 1862. In early 1864, Rose Gates College, being used as a hospital, was burned, as was the depot containing 100,000 bushels of corn.

After leaving the town, the Northern Army set fire to the fields, burning ungathered grain in a path from Okolona to West Point.

Returning through Okolona, the troop were met and defeated by General Nathan B. Forrest. General Forrest was wounded here and visited by his wife. His brother, Colonel Jeffrey Forrest, was killed near Prairie Mount, about six miles west of Okolona.

Temporary hospitals in Okolona, churches, schools, or homes served those wounded in battles at Shiloh, Corinth, Brices’ crossroads and Okolona. The third raid on Okolona occurred in January, 1865, just months before the end of the war. This time the “Yankees” set fire to the town, totally destroying every store. There are some private homes remailing in Okolona that pre-date the Civil War.

The land Deed Records and most of the other public records of Chickasaw County were burned by the Union Soldiers during the Civil War. Hearing that Yankee Raiders were in the area, some citizens, fearing that the courthouse in Houston would be burned, loaded the records on an ex wagon and started to carry them to a safe place. As the wagon traveled southeast on the Houston and Starkville Road, it was met by a small detachment of raiders. The records were seized, piled beside the road and burned. This took place on April 21, 1863. It is ironic that the courthouse was not burned.

By 1866, the population and commercial interests of the part of the county in which Okolona was located, east of Chuquatonchee Creek, had increased so that in response to the requests of its people, the Legislature enacted a law dividing the county into two judicial districts. The eastern part of the county was designated as the Second Judicial District while the western part is the First. It was further provided that equal terms of Circuit and Chancery Courts be held in each district, one in Okolona and one in Houston.

Baptist, Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian and Christian church congregations of whites had all been established in town by the end of the 1850s. The locations were later changed. When first built, three of them, the Baptist, Methodist and Episcopal Churches were located on the corners at the intersection of Main Street ad Church Street (Highway 245)-thus the naming of Church Street.

The building to house the First Baptist Church in Okolona was completed in 1849. It was located n the northwest corner of Main and Church Streets. The building was a simple square-cornered one, 60x20 feet in size with two doors facing Church Street and three windows on each side. It was never ceiled. The new worship house held regular services twice a month.

In 1895, the old Baptist Church building was sold and a new building erected on the southwest corner of Main and Gatlin Streets. In 1924, the congregation again realized the need for a larger building with plenty of Sunday School rooms. The modest 1895 building was replaced with an imposing three story brick structure in the same location.

The Methodist Church in Okolona was also organized sometime in the 1840’s. Around 1846 or 1847, the lot on the southeast corner of Main and Church Streets (Hwy 245) was donated to the Methodists by Mr. John Adam Lagrone and a house of worship was built there.

The structure was 444x36 Feet in size. Near the close of the Civil War this property was disposed of, or in some way lost. The congregation worshiped for some time in a downtown building. A list of the membership in 1871 shows members joining between 1857 and 1871. There are 53 members listed, plus a list of colored members. The first entry reads, “Thomas B. Shearer, L.D. (local deacon), By letter, 1857.”

The above-mentioned, Mr. Shearer’s descendants would, in the later half of the 1900s, set up a trust fund, the Rockwell Foundation, that would give large sums of money to projects in Okolona. Although none of the family has lived here for generations, things like the Shearer-Richardson Nursing Home exist because of their family ties. Okolona’s Public School District was the first fully air-conditioned one in Mississippi, thanks to the Rockwell Foundation.

In 1865, a two-story brick church was built on the same lot as the original Methodist Church. Then, in 1878, the congregation authorized General W. F. Tucker to secure a lot for a new church. The church that resulted was an elegant little church on Olive Street which was later sold to the Christian Church. In 1908, the present church was completed on the southwest corner of Main and Olive Streets

One of the more spiritual services ever held in Okolona was the planting of a “Prayer Tree” on the lawn of the Methodist Church on Thursday morning, April 15, 1954. Rev. James A. Grisham was pastor of the church at the time. His friend, Rev. Thomas A. Carruth of Nashville, a member of the Board of Evangelism was conducting a revival at the Okolona church. With this tree planting and the revival, the Prayer Life Movement that spread around the world was begin. The “Okolona Messenger” reported that “Although the panting of the tree was part of the Spiritual Life Mission in the Methodist Church, it was in reality a community program. Members of all denominations were present and the Rev. B.L. Mohon, pastor of the Baptist Church ad Rev. L.A. Holley, pastor of the Presbyterian Church, led the prayers in the dedication.

The Parish of Grace Episcopal Church was organized in 1851. The first church was located on the corner of Church and Main Street. The Church, a simple, unassuming structure, was built by slave labor. It was completed in 1852 at a cost of $1,250.00

On March 1, 1859, a house and lot were purchased for a rectory and grounds. A gift later that year of an adjacent chapel and burying ground was made to the church. The chapel was destroyed by fire during the Civil War. Also, in 1860, Rose Gates College, a seminary for young ladies, was given to Grace Church. The sale of these properties later made possible initial funding for a new church.

In 1877, the old church was demolished by a storm. The cornerstone, the Bible and some furnishings were preserved. The chandeliers from the old church were given to the Presbyterians. In 1906 a few of the church leaders determined to build a new church. Two of the gift lots of the old church were sold for funding ad the third became the location of the new church. L.L. Hodges was in charge of all financial arrangements. Miss Frances Abbott was the leader of the women in the effort. Bishop Thompson, second Episcopal bishop of Mississippi visited England and brought back with him building plans with which to make the new church building a replica of an English chapel. Bishop Dubose Bratton consecrated the new church in 1909.

There are records of Christian (the denomination) Churches in Chickasaw County as early as 1852. However, no record of one in Okolona exists until 1893. M.F. Harmon held what is remembered as the first revival by the Christina Church in Okolona. The old Methodist church, later purchased by the Christian Church, was borrowed for the meeting. The revival resulted in the organization of a church with a total of seventeen members. The Harrell family was very instrumental in holding this congregation together.

A lot on Main Street was purchased for the purpose of building a church there. However, the congregation was too small to raise the money and continued to meet in various buildings. Finally, in 1923, largely through enthusiasm generated by another revival, the church became more prosperous. The old Methodist church on Olive Street, which for some time had been used as a residence, was bought and again became a house of worship—this time for the congregation of the Christian Church.

In the 1850s some of Okolona’s settlers from Virginia, Tennessee and the Carolinas felt that they needed a church of their ow faith. They invited a Presbyterian preacher, Mr. Caruthers, from Houston, MS to help organize a church in Okolona. They assembled in the Methodist church on a sabbath in 1856 and formed their own Presbyterian church. It came into existence with twelve charger members. They mention a store owned by one of the members, a Mr. White. The membership grew and a building was feasible. Around 1859. A vacant lot was secured on the corner of Jefferson and School Streets. After the Civil War and during Reconstruction, the church suffered a loss in membership and finances. But about 1870, the church was able to get a regular pastor, Reverend Love.

In the 1880’s, a lot was secured for the Presbyterians from the Myers Estate and a new building was constructed on Man Street. The second Presbyterian Church was modeled after the first, since the same timbers were to be used.

In 1807 Mt. Pisgah Methodist Church was established as the first church solely for blacks in Okolona. The organizers were Issac Maywether, C.B Brown and a Mr. Gates. Services were held three times on Sundays—Sunday morning service, afternoon women’s service and evening service. It served also as the first school for black children to attend. Mrs. Fannie Carter was its teacher. So beloved and remembered was she that, when a public high school was finally built in 1959, it was named for her.

In 1880 John Groton was pastor, but those who served before him are unknown. The church building for M. Pisgah, in its present location on North Gatlin Street, was constructed in 1896 under the pastorate of Rev. M.B. Clay. The Upper Mississippi Annual Conference convened at Mt. Pisgah in 1937. In the 1990s, a larger and more modern church was built, again on North Gatlin street.

At one time, Dr. M.D. Conoway was pastor of Mt. Pisgah. Later, after integration and the church merger, he would be District Superintendent for the United Methodist Church. Mary H. Penn of Mt. Pisgah, who served as Dean of Students at Okolona College and as a Jeanes supervisor over the schools in the county, became a diagonal minister. Her daughter is an ordained minister and bible college teacher in Kansas City.

According to research, the earliest Baptist Church for blacks in Okolona was organized by Ambrose Henderson in 1868. The structure that occupied the present location at Jefferson and Olive was built in 1887. It was occupied until the present church was constructed in 1974. There were two Baptist Churches in the beginning, Second Baptist Church on the hill (on Meridian Street) and M.U.B. Baptist churches decided to unite and organize one church to be called Calvary Baptist. On the eighth day of May 1920, the merger was completed with the trustees of both churches signing the deed. Services were held in both church buildings. Sunday School was held in the building on the hill and church services were held in the other. After the building on the hill was condemned, all services were held at the building at Jefferson and Meridian Streets. The building on the hill was later torn down and Calvary Baptist Church parsonage was built. The present-day church, built in 1974, is at the corner of Jefferson and Olive.

The original Catholic Church in Okolona was dedicated on September 23, 1883 and named Our Lady of Good Help. This original church, located on the corner of Washington and North Olive was destroyed by a storm on June 4, 1911. From 1911 to 1922 Catholics met in homes to celebrate Mass. Church records note that local Catholics began raising funds and looking for a site on which to build a new chapel in 1917.

By 1922, the new church, St. Theresa’s, on the corner of Silver and Monroe was built and dedicated. In 1926, Father Robert, the pastor from Tupelo, wrote to the bishop requesting to sell the original property to the city of Okolona to be used for a school for “Negro” children.

From its beginning until 1965, St. Theresa’s was served by Benedictine priests from Cullman, Alabama. In 1965, the Glenmary Home Missioners assumed responsibility for Catholic Communities. In Monroe, Chickasaw, Pontotoc and Union Counties and thur over saw activities at St. Theresa’s. From 1965 to 1985, a variety of attempts was made to serve Catholics and others in Okolona. These included a clinic for poor people, pastoral outreach, a Boys’ Home and a “Help in Housing Project”.

Although the Catholic congregation in Okolona has become very small, their work continues. Beginning in the 1980s, under the leadership of Sister Liz Brown, a group of nuns of the Sisters of St. Joseph and Franciscan orders have coordinated a mission service in the town. Through such endeavors as after school tutoring and summer programs, both social and educational, they minister to the poor and minorities.

Okolona’s early leaders were interested in education their young people from the very beginning. Okolona’s first public school was a one-room cabin built in about 1840 on property belonging to John Adam LaGrone. In 1850 a two-story structure was built by W.G. Mabry, Sr. to replace the log one room schoolhouse. It has an entrance hall, study hall and three classrooms on the ground floor. The second floor served as a home for the principal and his family and a dormitory for girls. During this same time, a primary school for boys was conducted in the basement of the Presbyterian Church.

In 1853, W.F. Tucker, who would later serve as a general in the Confederate Army, founded Okolona’s first private institution, Okolona Male Academy. General tucker both taught and practiced law. Jonathan Smith, an Episcopal clergyman, established a female academy one year later. Both schools were used for other things during the war and were destroyed later.

In 1870, a brick building for a boys school was built in the northern part of town on School Street. In 1877, a private school for girls weas opened by Miss Leidy Matthews on South Gatlin Street, near Main Street. Okolona Male and Female College was built in 1890.

The public school building, around fifty years old, was replaced by a larger, and more modern structure. The building was completed September 27, 1890, and was a “grand structure of brick”, 80 feet by 110 feet. It is interesting that at that time, in addition to Ancient Languages, the languages of French, German, Spanish and Italian were taught.

This “new” school was replaced in 1924 by a three-story building that still stands today on the corner of Main and Church Streets. It was built on the same location as the previous building. W.G. Mabry, Jr. was the architect. From 1929 to 1944, A.W. James served as superintendent of schools and during that time a band building, a football stadium and a superintendent’s home were built.

In 1957, a $700,000 expansion program for the schools was inaugurated. This involved a $450,000 district bond issue and a $250,000 grant from the State of Mississippi. Included in this project was a new elementary school on Church Street adjacent to the existing school and renovation of the three-story building erected in 1924. This also include the building of a new school for backs, the afore-mentioned Fannie Carter High School.

From the diary of G.H. Babbitt, born in Okolona in 1877, an entry on August 11, 1897 tells of electricity coming to Okolona. He writes, “The lights were turned on all over the city tonight. We were at supper when the fact was announced and as soon thereafter as convenient, we went around town to see the sights of the town being lighted up by electricity. Everybody out on the street to see the sight.”

Okolona was a socially prominent town in days past-but it also felt a strong sense of obligation to serve not only the community, but state and nation as well. In 1898, when ladies from just six Mississippi towns answered the call to meet in Kosciusko to form the Mississippi federation of Women’s Clubs, ladies from Okolona were among them. In fact, two Okolona ladies have served as state president of that organization. They were Josie Frazee Cappleman, 1902-1904 and Catherine Haley, 1929-1930.

Through the years at various times, thirteen Okolona clubs have come and gone in the MFWC, but two have stood the test of time. The Lanier Club was organized in 1898 and federated in 1899. The Twentieth Century Club was organized and federated in 1919. One of many black organizations that have served our community is the National Council of Negro Women. All of these organizations contribute time, money, energy and talent to serve their community in many areas. Both blacks and whites have long had outstanding chapters of the Masonic Order and the Eastern Star.

Again quoting Mr. Babbitt’s diary, on April 21, 1898, “the U.S. is at war (the Spanish-American War). He writes, “Excitement high in this place and all the boys are talking of enlisting, among them, C. Ivy, Jr.”

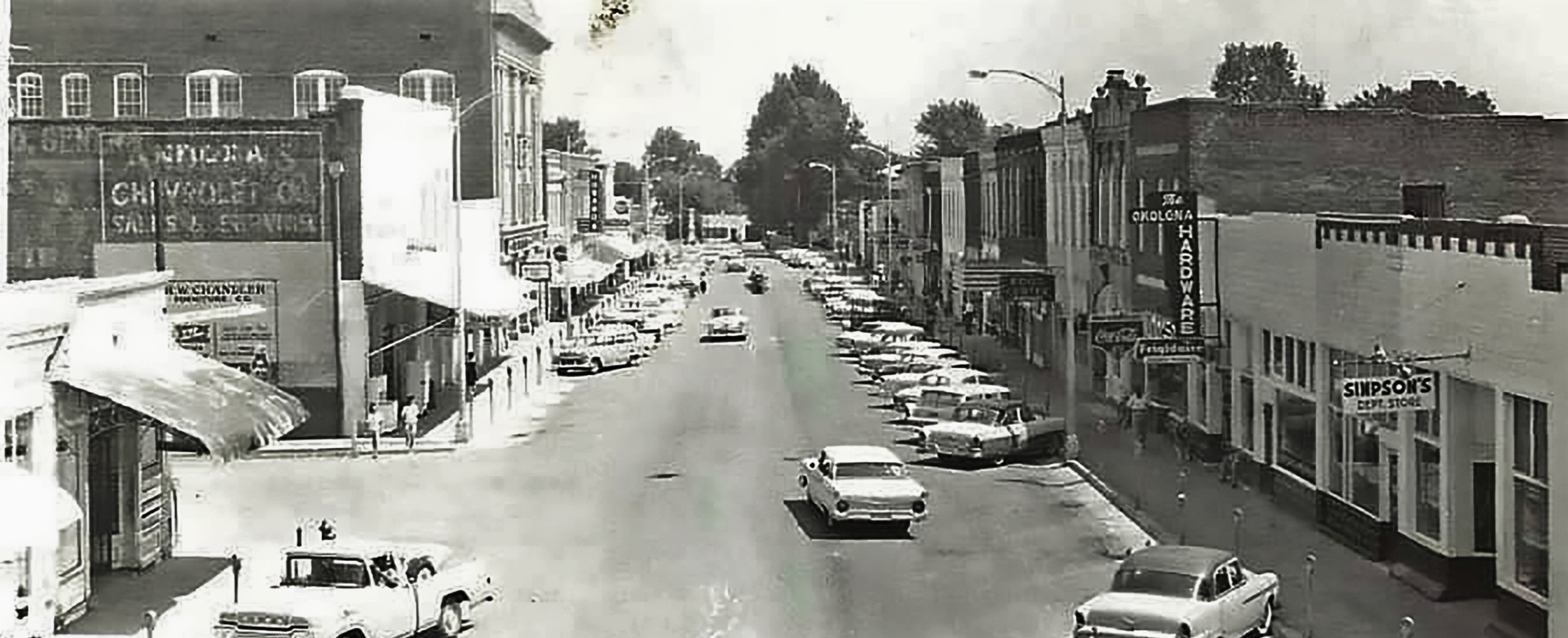

By 1900, Main Street was much as it is today, as far as there being a long row of buildings on each side. But the street itself was dirt (or mud, depending on the season) with board walks on each side for pedestrians. Three concrete walks were provided for people to conveniently cross the street. In the early 1900s there was an iron water well on Main Street that was 900 feet deep. It was pumped by a gas motor. The well was capped in the 1950s. There was also a concrete watering trough for the horses.

A map sketched of the downtown area in 1904 shows over forty businesses. Among them were interesting types of establishments such as blacksmith shops, an ice cream factory, livery stable, saddlemaker, hat shops, an opera house, Chinese laundry, meat stores and hotels. And there were the usual dry goods, general merchandise, hardware and furniture (caskets sold there also) stores.

Several businesses were labeled “colored” on the map and were owned by families who remained in business and prominent in Okolona for many years. These businesses were located primarily on the north side of Main Street west of what is today Olive Street. Chief among them was Charlie Gilliam, who was in business for over seventy years.

By the time of that 1904 drawing, the Baptist Church had moved to its present location although not the latest building. The Masonic Temple and Court House were where they are today, on Main Street with businesses located beneath them, just as Stewart-Harris is there in the year 2,000.

The Okolona Messenger was already in business. One or more papers have been published in Okolona continuously since 1849. In 1876, Okolona regularly published three newspapers. The “Chickasaw Messenger” was a weekly newspaper that was established in Houston, MS in 1872 and moved to Okolona in 1876 with Captain Frank Burkitt as the editor. It was changed to the Okolona Messenger in 1900 when it passed into the hands of Abe Steinberger and Sons. It has operated continuously, though changing ownership several times over the years. At the present time it is owned by Mr. and Mrs. Murry Blankenship.

Most of the merchants’ names are but distant memories at best to only a few people ow living in Okolona. R.W. Chandler Furniture and Undertaking was located on Main Street then. Almost a half-century later a grandson, by the same name, owns his own prosperous furniture business in Okolona. And there is Walter Smith Hardware on the 1904 map exactly were Fisher Hardware and furniture is today. A hardware store has been in that location ever since. The old cash register, no longer, in use in that store, has the bill of sales taped underneath it. It reads, “W.G. Stovall Hardware Company, July 28, 1924”.

If a person walks down either side of Main Street today, he can see signs of some of the businesses that existed on that 1904 map. In the sidewalk on the south side, where Roger’s Furniture is today, are the words “Parchman Brothers”. On the north side, in front of Excel Commons, it reads “J. Rubel and Company”.

In 1904 there were two hotels and two banks downtown. Later there were even more, until the Great Depression changed things. The map had a notation listing other assets as the city steam electric plant and water system, M and O Railroad, the Houston Railroad, railroad coal shoot, ice plant and four cotton gins. The last cotton gin in Okolona closed in 1977.

Shortly after the turn of the century, Okolona had a phone system. Indoor plumbing brought flushing toilets, which replaced old outhouses. The city’s sewage system was installed between 1912 and 1915.

Main Street was a gathering place for the townspeople, as well as farmers from nearby, on Saturday nights. Entire families would come to town for supplies and stay to socialize. This practice actually continued until the 1950s where television and air conditioning made staying home more desirable.

In 1907, the first “horseless carriage” (automobile) appeared in Okolona. It was a one-cylinder Cadillac owned by Dr. D.F. Morgan. Afterwards, two red one-cylinder Maxwells came to town and in 1912 Okolona had four Studebakers.

Through the efforts of local leaders, primarily A.T. Stovall, Okolona received the money for a Carnegie Library. Mr. Stovall first contacted the Carnegie Foundation in 1911 and in 1914 the library was built.

In 1917, World War I captured and held our town’s, as well as the nation’s, attention. Young Okolona men of both races served in the conflict. On June 5, 1917, all men in Chickasaw County between the ages of 21 and 31 years of age, were required to register for the draft. When the war ended on November 11, 1918, only five men from the entire county were reported to have died in the war. In Okolona, a National Guard Unit was formed to aid in the war effort. Fifty-eight men composed this unit, with Lieutenant George Ed Allen as commander. This unit disbanded int eh aftermath of the war. In the early 1950s another Mississippi National Guard unit was organized here.

With the Great Depression beginning in 1929 and lasting throughout most of the 1930s, Okolona was hard hit. All three banks closed and none existed at all for several months. Lowell Thomas, in one of his broadcasts, called Okolona “the hardest hit town in the nation.” Again, the town had to take heart and rebuild financially.

In 1934, the only payroll in Okolona was about $8,000 monthly for what was then the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. The American Legion, the businessmen and the five Federated Women’s Clubs joined forces with the city and in November of that year (1934) founded the Okolona Chamber of Commerce. Federal programs such as the National Recovery Act and the Federal Land Bank helped recovery. A new bank, the Bank of Okolona, under the direction of J.E. McCain, became Okolona’s only bank for 36 years. Today, there are again two banks serving the community. In 1967 First Citizens National Bank of Tupelo opened a branch in Okolona. Today it is a branch of the Peoples Bank and Trust Company.

Around 1935, to rebuild its economy, Okolona experience ed a new “air of progress and prosperity apparent everywhere” with its “Progress Chart.” Located on a vacant lot beside City Hall on Main Street, the chart was drawn up by the city’s Chamber of Commerce, which at that time was newly formed. It was erected to serve as a constant reminder to the citizens that the town was moving ahead and reaching its goals. On the chart were sixty squares, each with a different goal for the town. Some of the achievements were: building a new cheese plant, opening a movie house, acquiring a new hotel.

Okolona, which had been known as “The Pride of the Prairie” or “Queen City of the Prairie” now became known as “The Little City That Does Big Things”. It has been commonly accepted that this title came about because Okolona was the quickest town in the nation in raising its World War II Bonds Quota, but here are others who say the nickname was here before that.

During World War II, citizens dedicated their services and, many of them their lives, to the nation’s effort. At least one family, the Hal Jollys, lost more than one son (two) fighting for the United States of America. Many from Okolona got jobs In the large defense plant at Prairie, MS. This plant, to build ammunition for the Armed Services, was 20 miles away and was opened in 1942.

Following World War II, Okolona began a period of growth in a more modern world. No longer would it be only a town of small businesses serving an agricultural area. More industries began to locate here and life was changed.

Foremost among these industries that came in the 1950s was the large furniture manufacturing company owned by Morris Futorian to build “Stratoloungers”. These reclining chairs were new on the scene. It is interesting to note, that from the original furniture factory here, the entire northeast area of Mississippi has become a center of furniture production. This was largely because people wo had worked for Futorian gook their knowledge of the business and created new factories. At one time in the 1980s, Okolona alone had 27 furniture-related industries. Other towns in northeast Mississippi have become very active int e furniture business, and the Tupelo Furniture Market is one of the foremost in the nation.

Also, in the 1950s, Delta Trouser opened making men’s and ladies’ pants. Its owner was E.E. Davis. These large-scale operations were something entirely different for the people of Okolona. They brought in new people and gave a different kind of job to older residents. Many people from the farms came into town to work for hourly wages. The timing was significant, for new farm machinery was replacing a large number of agricultural workers. Also, lots of small farmers and sharecroppers were finding they could no longer earn a decent living from the land.

These new industries had hundreds of jobs to offer. Not all the workers were from the Okolona area. People drove from surrounding counties to work during the day. This boosted the local economy. On payday, many of these workers spent a good portion of their check in Okolona. They opened charge accounts in the local stores and generally helped the economy.

In the 1930s and 40s, hospitals were really small clinics. Dr. B. DeVan Hansell had a clinic above the Bank of Okolona. Dr. Armon F. Wicks had one just east of that on the corner of Main and Silver Streets. In the 1950s a large, modern (it was at the time) hospital was built on West Drive. Since then, the Shearer-Richardson Nursing Home and another hospital have been built, adjacent to the one of the 1950s. they face Monroe Avenue.

In the 1930s and 40s, the minority citizens of Okolona enjoyed not only their educational system, which made cultural and social activities available but services were also provided by their own. They had their own lawyers, doctors, mechanics, home decorators, plumbers, barbers, and seamstresses.

Among the doctors were Dr. Theodore Fykes, a dentist with his office on Jefferson Street and Dr. Charlie Wheeler, a medical doctor whose office was on the corner of Washington and Meridian Streets. Around 1950, the last black doctor to serve the people of Okolona, Dr. Francis Burton, lost his life when the large sale barn on north Olive Street burned.

Blacks also served as excellent chefs for the diners of the G M and O passenger trains and the hotels in town. The passenger trains, especially the “Rebel” which came through around ten o’clock at night, were a thing of great interest. Townspeople would go down to the depot just to watch them come through. At that time, a good many people were leaving on the trains to “go North”. It was also the main mode of transportation for visitors from other towns going to and from or for locals going to visit other places.

During the 1930s, 40s, 50s and 60s, Okolona’s Wilson Park became known as the “Playground of North Mississippi”. The Commercial Appeal, Memphis, it its Sunday, June 12, 1949 edition, gave a full page to pictures and write up about the recreational facility. Weekend after weekend, families, church groups and others came by the busloads and cars to spend a day at this large area devoted to good, clean fun. It was very unusual for a town as small as Okolona. The staff correspondent of the Commercial Appeal, after spending a day at Wilson Park wrote, “For Okolona has just about what it takes to make a contented citizenry and cheerful children.”

The first earth for the swimming pool was turned in 1929 by Mr. H.S. Wilson, a foreman of the old M and O Railroad roundhouse here. Mr. Wilson was mayor of Okolona from 1927 to 1936. Having moved to Meridian in 1939, he died on June 2, 1940, the day Wilson Park was to be dedicated to him. His dream was kept alive by others after that.

In that same newspaper article mentioned above, the writer says, “What \is Wilson Park? It’s 75 acres of oak-shaded land just south of town. It’s a swimming pool 60 feet wife and 178 feet long, one of the best equipped in the South. It’s a five-acre lake stocked with bream and bass. It’s a picnic grounds with tables, grills, barbecue pits and converted shelters to be used when it doesn’t rain. It’s a pavilion with a dance floor and a juke box where the youngsters gather to jitterbug if they like. It’s a church where the members of three denominations gather each Sunday night during the summer to worship God. And it’s Heaven on a hot day.”

In addition to all the activities at Wilson Park listed above, for a period in the late 1940s and early 50s, Okolona even fielded a semi-pro baseball team. Young men playing for the colleges in the state would hire on for the summer with a league team.

Former mayor Harvey Lee Morrison was quoted as saying of our town in 1949, “We might not have the best of everything, but we think we have.”

Right now, in the year 2000, Okolona’s future seems uncertain. There are not as many businesses on Main Street, the schools have faced crises and some of our industries face an uncertain future. But remember, this little city has faced hard times and challenges before and has come back each time stronger than before.

A postcard for Wilson Park in Okolona, c. 1930–1945